Can a single broken window lead to the decline of an entire neighborhood, and can tolerance for petty crimes contribute to the degradation of society as a whole? Supporters of the Broken Windows Theory believe this is entirely possible.

According to this theory, there is strong conformity within all social groups—most people adopt the group’s opinion, even if it is incorrect. Now imagine a society where violations constantly occur, their consequences go unaddressed, and the perpetrators remain unpunished. More and more people will adopt the same behavior: if others can do it, why can’t I? Another broken window will inevitably appear next to the first one. Conversely, in a society where order is strictly maintained and is a social norm, violations will become increasingly rare. From a psychological standpoint, the Broken Windows Theory seeks to explain how the surrounding environment shapes perceptions of norms and influences human behavior.

There are strong arguments on both sides of this theory. In this article, we will examine the pros and cons to understand whether the Broken Windows Theory can truly explain many aspects of societal development and be applied for the greater good.

The Essence and Application of the Broken Windows Theory

The theory was formalized by American political science and criminology scholars George Kelling and James Wilson. In 1982, they published an article explaining their idea: if a setting shows signs of neglect (e.g., broken windows, litter, frequent violations),it signals to society that order is not being maintained. This, in turn, contributes to an increase in serious crimes and antisocial behavior. In other words, a lack of order fosters an atmosphere of impunity that encourages further violations.

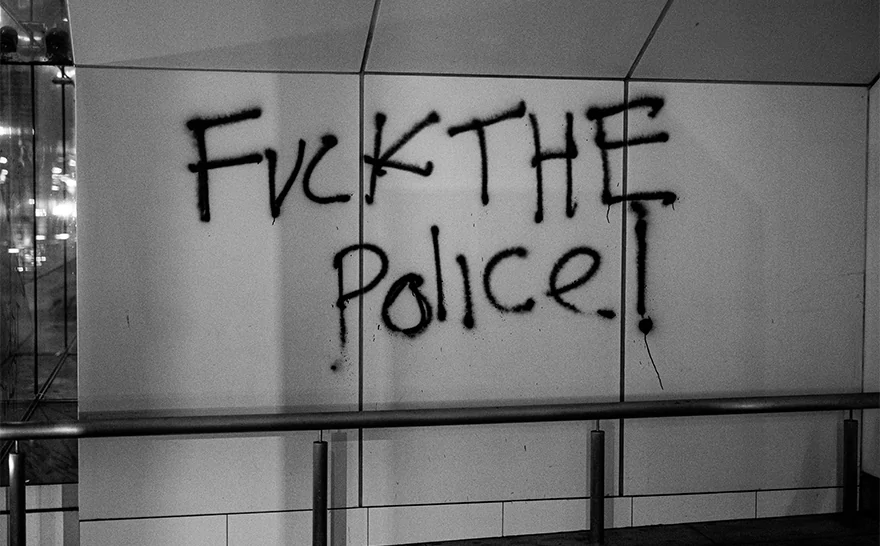

A broken window in this context is a metaphor for any visible deviation from established social and legal norms. These can include:

- graffiti and obscene inscriptions on walls;

- vandalism and damage to private or public property—flattened tires, broken traffic lights, etc.;

- uncollected trash and animal feces on streets;

- improper car parking;

- loud music during nighttime hours;

- public drinking and antisocial behavior in public places;

The authors argued that in such conditions, the likelihood of similar or other violations increases significantly, raising social tension and making the community feel unsafe. Law-abiding citizens—those who pay taxes, follow laws, and respect others’ property—will move to more respectable areas, leading to declining property values and business withdrawal. This process doesn't happen overnight—it can take years or even decades.

According to the authors, the theory also works in reverse. Timely road and building repairs, the creation and maintenance of public spaces, and increased law enforcement can help reduce crime and make neighborhoods more livable.

By the late 20th century, the Broken Windows Theory had gained significant popularity among city councils in the U.S. (and beyond),influencing budget allocations. Local governments became more willing to invest in urban design, lighting and building repairs, graffiti removal, trash cleanup, park improvements, sports facilities, public libraries, and more. Many municipalities adopted a "zero-tolerance" policy for petty offenses such as illegal vending, panhandling, loitering, and neglected properties. Some even implemented special police programs. To "revive" troubled areas, special funds were created, and local businesses received development grants. This policy genuinely transformed the visual appearance of many districts, making them more comfortable to live in.

Perhaps the most famous example of the Broken Windows Theory in practice is New York under Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg. Authorities declared war on minor offenses that had previously been largely ignored. Within a few years of implementing this policy, overall crime rates significantly dropped—not only minor violations, but also serious crimes like robbery and murder.

The theory also found application in the corporate world. In the 1990s, many companies tightened discipline, introduced strict dress codes, and imposed fines for tardiness. Results were mixed and, of course, depended on many factors, but some leaders attributed success specifically to increased control and the implementation of strict workplace rules.

Experiments Supporting the Theory

James Wilson and George Kelling observed New York subway stations and found that dirty, graffiti-covered stations attracted more petty criminals and offenders than cleaner ones. When these stations were cleaned up—trash removed, graffiti painted over, and fare evasion fined—crime levels dropped significantly.

Kelling and Wilson were not the first to suggest a link between visual order and antisocial behavior. They built on previous research, particularly the famous experiment by American psychologist Philip Zimbardo. He left two identical license-plate-less cars in very different neighborhoods: affluent Palo Alto, California, and unsafe Bronx, New York. In the Bronx, the car was quickly dismantled for parts—within minutes. In upscale Palo Alto, the car remained untouched for a week. But once Zimbardo broke one of the windows, the car was stripped within 24 hours. This led him to conclude that visual signals can indeed intensify the urge to violate social norms. The broken car window signaled that order was not being maintained and antisocial behavior was acceptable.

In 2008, Dutch researchers led by Kees Keizer conducted a series of intriguing experiments. For example, at a bike parking area, they posted a sign prohibiting wall drawings and attached a flyer to each bicycle. Cyclists had two options—take the flyer with them or litter it (trash bins were deliberately removed). When order was maintained and walls were clean, only 32% littered. But when the walls were covered in graffiti (thus violating the posted rule),69% littered. This showed that one rule violation can strongly influence people to violate another—like not littering in public spaces.

Criticism and Refutations

The Broken Windows Theory has greatly influenced urban management and development in many countries. Nevertheless, it has been subjected to well-founded criticism for several reasons:

- First, the experimental results were called into question. Many studies failed to confirm a clear causal relationship between visual disorder and crime rates. The two may correlate, but that doesn’t mean one causes the other—they could both stem from other factors, such as income levels.

- The practical application of the theory inevitably involved many variables (economic, demographic, and technological changes occurred during implementation),making it impossible to isolate the pure effect of Broken Windows interventions.

- The “zero-tolerance” policy justified harsh and often unlawful police actions, especially against racial minorities. This increased social tension and led to a surge in public distrust of law enforcement.

- Mass arrests for minor offenses overwhelmed the judicial system and increased the prison population.

- The theory focuses on symptoms and merely masks problems without addressing root causes of crime—such as poor education, lack of housing, unemployment, and more.

Many scholars argue that the Broken Windows Theory never had solid scientific backing. For example, researchers from Northeastern University conducted a meta-analysis of over 100 studies and found no evidence supporting the theory. Instead, they found systemic methodological flaws in the studies that supposedly validated it.

An important issue is the theory's contribution to racial stratification. In New York alone, police programs based on the theory stopped millions of people, 87% of whom were Latino or African American. This preventive policing led to racial discrimination and the violation of civil rights for entire ethnic groups, predictably sparking mass protests.

What Actually Works

Despite the criticism, the Broken Windows Theory remains an influential concept in urban management and public policy. Of course, well-maintained public spaces improve comfort and positively impact people’s moods. But do they truly reduce crime?

According to many scholars, poor economic conditions are the true drivers of crime. For instance, this study by the University of Texas confirmed a direct link between crime rates and unemployment, lack of financial resources, and limited legal means of achieving success.

Looking more closely at New York, we see that crime rates started to drop in the 1990s just as residents’ incomes rose, poverty rates declined, and unemployment fell. Clearly, people who earn enough to meet their needs commit far fewer crimes. Notably, even after law enforcement programs were scaled back, crime rates continued to decline—something the Broken Windows Theory would not have predicted.

In conclusion, creating a safe environment is undoubtedly one factor in societal development. However, visual signals and tolerance for minor violations should not be seen as the primary causes of rising crime. The popularity of the Broken Windows Theory is rooted more in ideology than in scientific evidence.