Of course, most of us are certain that we live real lives. After all, we experience emotions, fall in love, build families, pursue careers, spend time with friends — and all that can hardly be unreal. But what if our eventful lives are actually unfolding inside a computer program that merely transmits electrical impulses to your brain? You probably thought of the Wachowski brothers’ The Matrix, but this idea is not new — its roots go back to the reflections of ancient philosophers.

Today, the question of whether we live in a simulation has moved beyond philosophy. The rise of computational power and advances in artificial intelligence make this possibility worth serious consideration. Many AI-generated videos are already almost indistinguishable from real ones, and modern video games have graphics so realistic that we couldn’t have imagined them a few decades ago. Will we be able to tell a computer simulation from reality in, say, 50 years if technology keeps advancing at the same pace? And what if humanity has already reached the point where creating realistic simulations is possible — and we are living in one of them?

In this article, we’ll explore the arguments for and against this scenario and try to unpack this complex topic.

Origins of the Simulation Idea

Plato described the famous Allegory of the Cave around 380 BCE. Prisoners can only see the shadows of objects passing behind them. For them, these shadows are the only known reality — they are unaware that their world is merely a projection of a more fundamental “true” world. Plato was the first to ask, “Can we be sure that we do not live in a world that is only a shadow of something greater?”

The Pythagoreans claimed that everything in the universe follows mathematical laws — meaning that behind visible objects lies a kind of code describing their state and functions. Many Greek philosophers (Parmenides, Heraclitus, Pyrrho) concluded that we cannot truly perceive reality because we encounter it only through the prism of our senses and experience. Therefore, in a strict sense, each person’s world is individual and subjective — and thus may differ from reality itself.

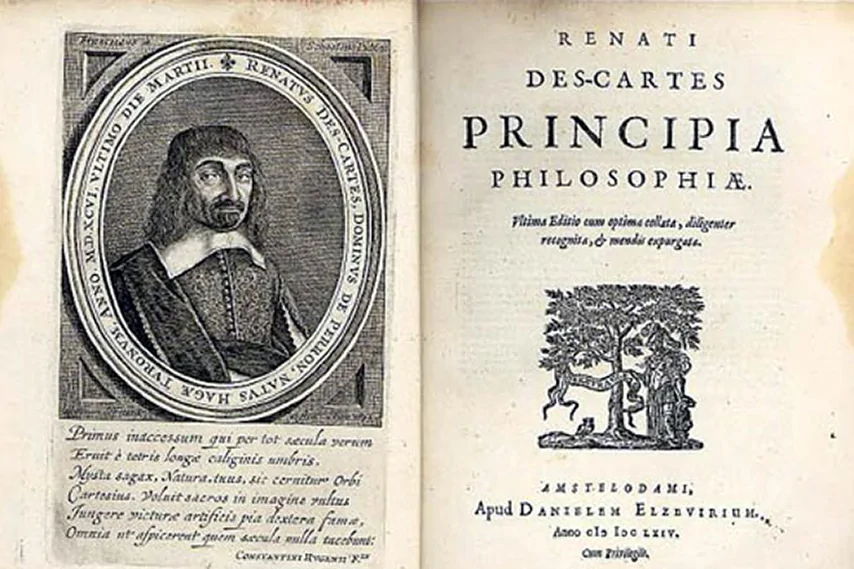

René Descartes went further. In the 17th century, he proposed the existence of a “malicious demon” — a powerful deceiver manipulating all our sensations. Descartes argued that we cannot be sure of anything if such a being could control our perception. His theory can already be considered a full-fledged concept of an artificial world — a precursor to modern simulation theories. The only difference is that today, instead of a demon, we speak of advanced artificial intelligence or an ancestor civilization.

Eastern philosophy developed similar ideas independently. In Hinduism, the physical world is described as an illusion that conceals the true nature of reality. In Buddhism, the surrounding world is a conditional reality, not an absolute one. Daoism teaches that the world changes every moment and that any attempt to describe it already distorts reality. The Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi questioned the boundaries of consciousness and the difference between dream and reality with his famous paradox: “Once I dreamt I was a butterfly, and I did not know — was I Zhuangzi dreaming I was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming I was Zhuangzi?”

Modern Formulation

In 2003, Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom published his paper Are You Living in a Computer Simulation? Bostrom argues that one of the following three statements must be true:

- Advanced civilizations go extinct before reaching sufficient computational power.

- Even after achieving such power, they are not interested in creating simulations.

- We are most likely living in one of those simulations.

The reasoning is straightforward: if a civilization develops long enough, it will eventually create computers capable of simulating entire worlds. There could be many such simulations, but only a few “base” civilizations. Thus, any randomly selected conscious being is far more likely to exist in a simulation than in the original reality.

Bostrom’s argument has a solid mathematical foundation. It relies on probability theory rather than emotional reasoning, which made his paper a serious subject of scientific debate — not merely a philosophical speculation.

Modern Supporters of the Hypothesis

Bostrom’s ideas resonated with influential figures in science and technology. Elon Musk often speaks about this topic, and his stance is quite radical. He stated that the chances of us living in base reality are “one in billions.” Musk refers to the pace of video game evolution: within a few decades, they’ve gone from simple Pong to fully immersive worlds. Soon, he argues, we’ll be able to create simulations indistinguishable from reality. And if humanity has already reached that point, countless such simulations may already exist.

Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson takes a more cautious position but also leans toward the simulation hypothesis. He estimates the probability as “quite high,” citing the rapid progress of technology. Tyson notes that if this trend continues, distinguishing simulation from reality will soon become impossible.

Arguments in Favor of the Simulation Hypothesis

Proponents of the simulation hypothesis have gathered a collection of facts that make one think twice.

Physical Features Suggesting Simulation

The most obvious argument is the fine-tuning of physical parameters that make life possible. For instance, if the electron’s mass differed by just a few percent, liquid water and DNA molecules could not exist. A slight change in gravity would prevent nuclear fusion, and stars like our Sun could never form. Therefore, many believe that the universe’s key constants appear to be “pre-set.”

Supporters also point to the observer effect in physics. An electron behaves like a wave until it is observed — once measured, it acts like a particle. This resembles how video games render content only when the player looks in that direction — why waste resources otherwise?

The speed of light — the ultimate limit for information transfer — might be seen as a technical constraint of the “hardware” running our simulation.

Technological Progress

In just 50 years, we’ve gone from primitive pixel games to hyper-realistic virtual worlds. Moore’s law held for about half a century, doubling computational power roughly every two years. Quantum computers promise exponential leaps, and artificial intelligence now generates humanlike content. If this trend continues, simulating reality is only a matter of time.

But what if we create simulations while already being inside one? That would form a kind of nesting structure — simulations within simulations within simulations. Statistically, most conscious beings would exist deep within such a recursive hierarchy, far removed from the original reality. This could explain the fine-tuning of constants: each level is designed by intelligent beings who deliberately set parameters suitable for life.

Supporters also cite optical illusions, déjà vu experiences, and the so-called Mandela Effect as subtle evidence of glitches in our “program.”

Scientific Research and Experimental Attempts

In 2012, a group of physicists led by Martin Savage at the University of Washington proposed concrete methods for testing the simulation hypothesis. Their idea was based on the assumption that any simulation must be finite and limited, and thus such boundaries might be detectable as small deviations in physical constants. They suggested that space in a simulation would be structured like a discrete lattice — similar to pixels on a screen. If that’s the case, high-energy cosmic rays should exhibit specific distortions while traveling through it. Results remain inconclusive: some anomalies have been found, but they can also be explained by astrophysical models. So far, there’s no scientific proof that our universe is simulated — but neither can this possibility be ruled out. This research revealed how extraordinarily detailed such a simulation would need to be. If our world truly is one, its resolution must be beyond any current means of detection.

Research continues: scientists are exploring whether spatial discreteness can be detected in experiments at the Large Hadron Collider. They are searching for deviations in particle scattering at extreme energies that might indicate a discrete structure of reality.

Counterarguments and Criticism

Despite the growing popularity of the simulation hypothesis, it faces serious criticism — both logical and practical.

Computational Constraints

The most obvious objection concerns the immense computational requirements for simulating an entire detailed universe. Physicist Robin Hanson, Bostrom’s colleague at Oxford, points out a fundamental problem: accurately simulating a system requires computational resources comparable to that system itself.

To simulate every atom in a human body would require around 10^27 operations per second — for one person alone. Simulating the entire observable universe would demand computational power exceeding the limits of any physical system within that universe.

Critics argue that a simulator cannot use more resources than exist in the simulated system. This creates a logical paradox: where would the matter and energy come from to power a computer larger and more complex than the universe it simulates?

Physicists also highlight the energy cost. Simulating quantum processes requires exponentially growing resources. Modeling a system of n particles means processing 2^n states. A system of just 300 particles would already require more states than there are atoms in the observable universe. Simulating a human brain with its 10^14 synapses seems computationally impossible.

Other Objections

If our civilization exists in a simulation, then the simulating civilization must be more advanced. In that case, why haven’t they already created even more sophisticated simulations — or moved on to other endeavors?

Mathematician David Pearson criticizes the statistical foundation of Bostrom’s argument, noting that it relies on unproven assumptions about probability distributions.

Another issue is the hypothesis’s fundamental untestability. Any experiment we perform takes place within the supposed simulation and thus cannot provide information about the external reality. If the creators of the simulation are intelligent enough to design a convincing universe, they likely built in safeguards against detection. Any anomaly could simply be interpreted as a quirk of natural laws rather than a “glitch.”

Critics also question why an advanced civilization would expend immense resources on a detailed historical simulation. They would likely use more efficient methods of studying history or entertainment — perhaps simulating only key moments or abstract models rather than full-scale replicas. This makes it less probable that we are living in one.

Moreover, our idea of what a simulation might look like is based on today’s technology. A real simulation built by an advanced civilization could operate on principles we cannot even imagine.

Neil deGrasse Tyson adds that even if we did find proof of living in a simulation, it might not change our daily lives. The laws of physics would remain the same — whether computed or “naturally” existing.

Impact on Culture and Popular Perception

The simulation hypothesis has gone far beyond academia and become part of popular culture. Its appeal has only grown as virtual reality and artificial intelligence moved from science fiction to everyday reality.

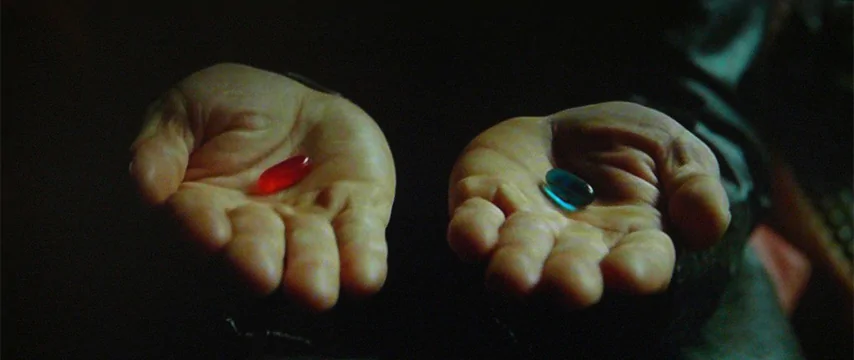

The Matrix was a turning point in popularizing the idea. The Wachowskis transformed a philosophical concept into a thrilling action film accessible to a mass audience. The red and blue pills became timeless symbols of the choice between comfortable illusion and painful truth.

Alex Proyas’s Dark City explored similar themes, emphasizing memory manipulation and identity. Tron imagined a world where programs possess consciousness and virtual space follows physical laws. Christopher Nolan’s Inception blurred the boundary between dream and reality, introducing the idea of multilayered simulations.

Communities on Reddit and YouTube channels dedicated to “proof of simulation” collect photos and videos of optical illusions and coincidences as supposed evidence of our world’s artificial nature.

Psychological Reasons for Its Popularity

Several factors explain the appeal of the simulation hypothesis. First, it gives a sense of uniqueness — the idea that we are not random but part of someone’s grand design or experiment.

Second, the simulation offers a modern reinterpretation of religious thinking: instead of gods, we have programmers; instead of divine plans — algorithms. It fulfills a need for meaning and purpose without requiring belief in the supernatural. When life feels unfair or meaningless, one can find comfort in the thought that “it’s just a game.”

Third, the idea resonates with modern lifestyles. We spend hours in virtual spaces and work with abstract data — the line between real and digital genuinely blurs.

However, feelings of unreality can sometimes stem from the psychological disorder of depersonalization/derealization, in which a person feels detached from reality and the world seems artificial. On our website, you can take a free DDR test.

Existential and Philosophical Questions

Questions about what makes experience “authentic” and how physical processes relate to subjective consciousness remain relevant regardless of whether the simulation hypothesis is true. If everything we perceive as real could be computer-generated, how does that affect the meaning of life and our moral values?

Traditional notions of life’s purpose rely on the assumption that our actions have real consequences in a physical world. We strive to make a mark in history, help others, create something meaningful. But if all of this happens within a simulation, do our efforts still hold value?

Existentialist thinkers might find the simulation hypothesis supportive of their ideas. If the world is illusory, then the only true reality lies within our inner experience and freedom of choice. We create the meaning of our existence ourselves — whether we live in a simulation or base reality.

If we indeed live in a simulation, who created it and why? This question gives rise to countless speculations, from scientific to religious. The most plausible creators might be our own descendants — using the simulation as a tool for historical study, with us as subjects of observation.

Another hypothesis suggests that the simulation was built by an extraterrestrial civilization studying humanity — one of many experiments designed to understand how societies evolve under different conditions.

Perhaps the simulation serves purely for entertainment — we are characters in a game or virtual reality. That perspective might seem degrading, but it doesn’t necessarily deprive our lives of meaning.

Conclusion

The simulation theory remains one of the most intriguing and controversial ideas in modern science and philosophy. One of its main challenges is its inherent untestability: any experiment we conduct would occur within the supposed simulation and thus yield distorted results.

We may never be able to disprove the possibility that our world is a simulation. Yet that shouldn’t paralyze us or strip life of meaning. Our subjective experience remains real to us, regardless of its origin — and even if we are living inside a simulation, nothing prevents us from living our lives as consciously as possible.