When a novel overturns notions about madness and freedom, it becomes more than a literary work. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey, published in 1962, and the cult film adaptation of 1975 by Miloš Forman is the voice of thousands of people suppressed by the inhumane approach to treating mental problems at that time.

The story of Randle McMurphy, who threw a challenge to the system, is a metaphor of an era in which the thirst for freedom and protest against established rules led to real changes for the better. In a world where “normality” is imposed by the system, and difference from the majority is stigmatized as illness, Kesey calls to abandon silent consent with hypocrisy. In Flying Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, he brings to the forefront the theme of medical violence—a special type of violence masked under care, treatment, and social good. The novel shows how psychiatric institutions turn into spaces where violence is not just allowed—it is legalized and presented as a manifestation of love for one’s neighbor.

In this article, we will figure out how One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest divided psychiatry into “before” and “after,” becoming the main symbol of the anti-psychiatric movement, and why this novel is still relevant in 2025.

Psychiatry as an instrument of control

In the 1950s–1960s, psychiatry in the USA was a dark chapter of medicine. Psychiatric hospitals more resembled prisons, were overcrowded with patients, and poorly funded. To end up in such an institution was quite easy—they placed people there for depression, anxiety, or simply those who did not fit into social norms. Patients were subjected to cruel procedures: electroshock therapy without anesthesia, put into insulin comas, subjected to lobotomy, a procedure irreversibly destroying personality. Diagnoses, such as “schizophrenia” or “hysteria,” were often given without solid evidence, especially to women, representatives of sexual minorities, or dissenters. Hospitalization could be lifelong, and patients’ rights were practically nonexistent.

Ken Kesey faced this reality, working as an orderly in the Menlo Park clinic and participating in experiments with LSD within the framework of a CIA research program. Observing the inhumane approach from inside the system, he was imbued with the idea that psychiatry more often did not heal but simply suppressed the will of patients. Kesey considered the clinic not a place of healing but a machine of discipline.

It is important to understand the general atmosphere of protest in the youth environment of the USA at that time, which influenced Kesey’s worldview: anti-war protests, the development of the civil rights movement and hippie culture, a huge drop in trust in the institutions of power. Against this background, the psychiatry system, holding hundreds of thousands of people hostage, became a symbol of repression.

The anti-psychiatric movement, gaining strength in this period, mercilessly criticized the established system but had popularity only in narrow progressive circles. Michel Foucault in History of Madness asserted that psychiatry is a form of power, isolating “abnormals” to maintain social order. Ronald Laing considered “madness” not an illness but a reaction to society, proposing humane approaches to treatment. Thomas Szasz (by the way, Ken Kesey corresponded with him) in The Myth of Mental Illness called diagnoses labels and forced treatment a violation of freedom. It was these ideas that found resonance in Kesey’s novel and could be conveyed to a wide public, and the film adaptation of the novel drove the last nail into the coffin of “old school” psychiatry. After this, ideas oriented toward helping patients came to the forefront, and, most importantly, under public pressure, the approach of authorities changed, and psychiatric hospitals stopped resembling prisons.

The asylum as a metaphor of society

The psychiatric hospital in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is not just a place of action. It represents a closed world in which the logic of violence is laid bare. Here, every element is subordinated to a single goal—suppression of individuality and fitting the patient to the model of “socially acceptable” behavior. Psychiatry, instead of treating, becomes an instrument of discipline and submission. In this context, the hospital is a model of an authoritarian society. Here, treatment becomes merely a means of expelling inconvenient character traits: disagreement, individuality, aspiration for freedom.

At the center of this world is Nurse Mildred Ratched, a symbol of total power. Her methods are bloodless but destructive: control through routine, moral humiliation, manipulations, and various forms of intimidation. Patients in this world are broken, fragmented people, voluntarily submitting to the order. They are divided into categories, which only emphasizes the dehumanizing approach. Kesey shows that, entering the clinic, a person becomes an object, not a subject of treatment.

Chief Bromden, the narrator, perceives the clinic as a huge machine—a metaphor of all-penetrating controlling power. Its goal is to erase the memory of who you are and replace it with a new, controlled identity. Bromden speaks of the “fog” that covers him and other patients—a clear image of psychic suppression and frustration. He is physically powerful, but his spirit is paralyzed. It is through Bromden that Kesey reveals the themes of suppression, self-renunciation, and healing. The image of the machine becomes especially sharp in scenes where the mechanism of personality transformation is mentioned. Characters who underwent therapy become “smooth” and “empty.” In this, Kesey shows the danger of institutional medicine devoid of ethics: it can conduct not healing but simple conformism.

McMurphy is dangerous to this system not because he is mentally ill but because he is uncontrollable, because he has not lost the sense of his own “I.” His appearance in the clinic is an invasion of chaos into the world of order. He breaks the rules, and his resistance exposes the mechanism of power: it is enough for one person to start thinking freely—and the whole system begins to crack at the seams. It is especially important that McMurphy is not a saint or a hero in the traditional sense. He is a gambler, a swindler, a person with a dubious past. In his traits, everyone can see their own flaws. But in conditions of moral emptiness, where power is masked as care, it is he who becomes the voice of truth. His protest is instinctive, it comes from a sense of justice, a desire to protect the weak, disgust for hypocrisy and double standards.

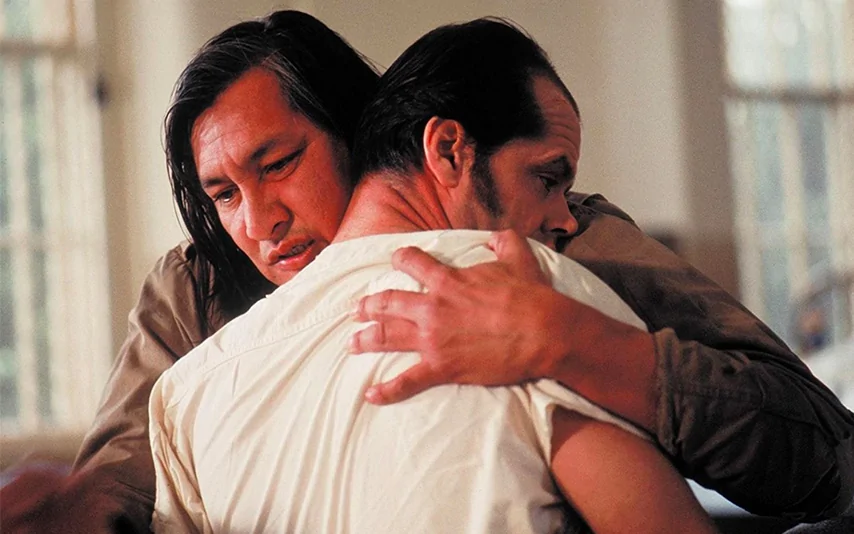

The appeal of McMurphy to Bromden as a personality carries deep symbolism. It is precisely this that launches the process of healing, and it is precisely this approach that Kesey opposes to the depersonalized systemic “treatment.”

Medical violence as the core of the novel

Electroshock therapy, medication suppression, forced isolation, and lobotomy were indeed part of everyday practice. It is hard to believe now, but many psychiatrists justified the use of such methods and insisted on their advantages.

Nurse Ratched is not a sadist in the classical sense but an impeccable executor of “good intentions,” a collective image of “old school” psychiatrists. She uses the language of medical ethics to justify suppression; her methods are “reasonable” and “humane”—but the result is the complete destruction of the patient’s personality.

Through the example of McMurphy, we see that the application of such methods is not medical help but punishment for disobedience. First, he is subjected to electroshock for refusing to recognize the authority of the head nurse. Later, he is punished definitively—with a lobotomy, which turns him into a physical shell without will. This is the culmination of medical violence in Kesey’s understanding: not murder, but the destruction of personality under the guise of healing.

Medical violence in the novel is violence with a diploma and protocol. It is in this that its destructive power lies. Thus, Kesey leads to an alarming thought: violence can be legalized, professionally and thoroughly documented—but this does not cease to be violence, only becomes stronger, and therefore—it is harder to stop.

The legacy of the novel and system reforms

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest became a social challenge of its time. Ken Kesey’s novel and especially its film adaptation by Miloš Forman played a colossal role in forming public opinion about psychiatry, forcing a rethink of the very essence of the attitude toward mental illnesses and psychological disorders.

After the film’s release, large-scale reforms of the psychiatric system began in the USA: unjustified hospitalizations and harsh methods of behavior correction were canceled, many psychiatric hospitals were closed, and the rest stopped resembling prisons. Thousands of patients left asylums to continue therapy at home and, with varying success, returned to ordinary life. Similar reforms affected not only the USA but also many European countries.

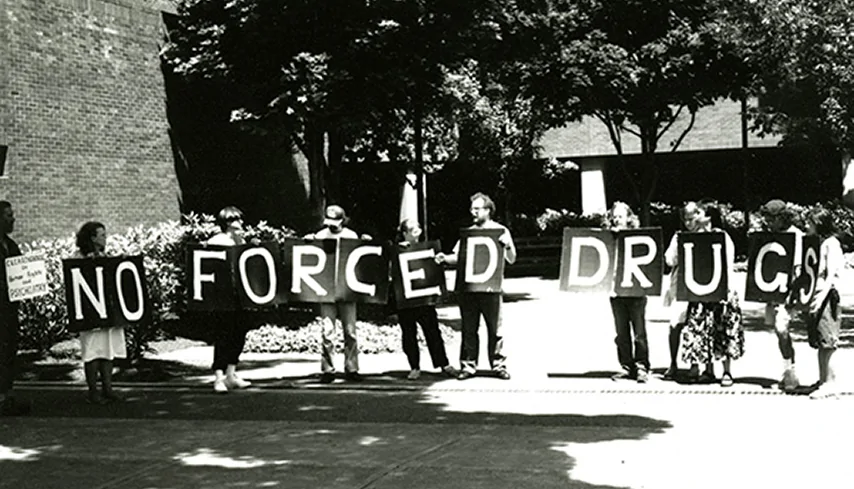

It is also worth noting the legal consequences: laws were passed regulating the use of electroshock and lobotomy; abuse of medications in psychiatric practice could now be interpreted as a violation of patient rights. Public movements and activist groups appeared, advocating for the rights of patients with psychological problems to treatment at home and participation in societal life.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest influenced the professional ethics of psychiatrists themselves. It forced many specialists to think about the boundary between treatment and suppression, between help and control. In medical circles, the novel became a painful but necessary point of reference. The novel and film became catalysts for the development of psychiatry and psychology. The monopoly of eminent doctors of the past on the only correct opinion was destroyed, which gave impetus to new discussions, research, development of new drugs, and the advancement of psychotherapy.

Of course, changes did not happen instantly and painlessly. But today it is hard to imagine a discussion about patient rights without reference to this work. It changed the attitude toward those who found themselves beyond “normality.” Kesey’s novel and its film adaptation not only reflected the sick side of society but also led to society’s actions for its healing. This is a rare case when a work of art not only exposes reality but also changes it for the better.