After a long search, an HR manager finally finds a candidate who perfectly meets the client’s requirements. Skills, competencies, experience — everything is ideal. The requirements were strict, and only one suitable person was found. Yet after the face-to-face interview, the client rejects the candidate. When asked why, the client explains: they didn’t like the candidate’s appearance.

This is one of many real stories shared by HR managers online. We truly tend to judge others based on first impressions. This cognitive bias is called the “halo effect.” The first impression of a person influences how we perceive their abilities and skills. That’s why attractive people often seem smarter and more competent than others.

In this article, we will take a closer look at what the halo effect is and how it affects our lives. We’ll explain when it can be harmful, when it can be beneficial, and how you can protect yourself from this bias and see people more objectively.

Why Does the Halo Effect Work at All?

Our brain seeks maximum efficiency with minimal energy use. That’s why we tend to take the easy, familiar path instead of inventing new ones. Familiar things feel safe and therefore more appealing. Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman proved that we have two systems of decision-making. The first reacts quickly but oversimplifies reality, often leading to mistakes. The second works much slower but provides more accurate results. Still, the brain usually chooses the first option — fast response and energy saving.

For centuries, our ancestors had to quickly judge whether another person was safe. Diseases like typhus, plague, smallpox, and syphilis often caused visible changes. Symptoms such as rashes, sores, and ulcers could signal illness and the risk of contagion. Avoiding such people increased survival. That’s why many of us feel discomfort when seeing clusters of holes — a phenomenon known as trypophobia.

On our website you can take a free trypophobia test.

By contrast, an attractive appearance signaled health — and thus safety in interaction.

Then stereotypes come into play. The human brain thinks in patterns, and that’s not necessarily bad. Stereotypes are a way to minimize energy costs. The quality of decision-making suffers, but usually not enough to matter. For example, stereotypes make us think that people wearing glasses are more intelligent, even though no link has been proven between eyesight problems and intelligence.

Whether we like it or not, beauty standards also shape our perception. Being like everyone else feels safer — it’s a herd instinct rooted in biology. A person who matches accepted beauty standards is more likable. Conversely, the further your appearance, clothing, hairstyle, hair color, height, or weight deviate from the average, the less attractive you seem.

Information overload in modern life also reinforces reliance on first impressions. With so much data around us, our ability to process new information decreases.

Read also: The Psychology of Choice: Why It Has Become So Hard to Make Decisions.

The first impression is highly persistent. Later judgments about a person largely depend on it. When we encounter facts that contradict it, we tend to ignore them. To save energy, the brain extends the first impression to other traits of the person. If we like someone, we assign them positive qualities simply “because.” Only when facts clearly contradict that first impression does critical thinking kick in.

On our website you can take a free critical thinking test.

It only takes seeing an attractive person in a business suit for us to immediately assign them positive professional qualities they may not actually possess.

History and Experiments

The existence of the halo effect was first noticed by American psychologist Frederick Wells in 1907. But the first to study it systematically and reliably describe it was Edward Lee Thorndike in 1920. He analyzed how superiors assessed their subordinates — in this case, American soldiers. Thorndike asked officers to rate soldiers on various qualities. He discovered that attractive soldiers consistently received higher ratings. The rated qualities — such as intelligence, physical ability, and leadership — were not logically connected to appearance. Yet attractive men were scored higher, as if surrounded by an invisible positive “halo.”

In 1946, Solomon Asch conducted his own experiment. He showed participants different photographs and asked them to judge the personalities of the people shown. The photos were of the same individuals — some flattering, others unflattering. The results confirmed the halo effect: participants rated people on attractive photos far more positively, attributing qualities like kindness, friendliness, empathy, and intelligence.

In 1974, American psychologists D. Landy and H. Sigall published a study that also confirmed the effect. Students were asked to evaluate essays, supposedly written by female freshmen. Some essays were good, others deliberately poor. Each essay was accompanied by a photo of a more or less attractive young woman. Even poor essays received higher marks if they were paired with an attractive photo — and vice versa.

Subsequent research has confirmed that the halo effect influences nearly all areas of human life.

How the Halo Effect Shapes Our Lives

The halo effect can help or hinder us as early as school. In 1968, Rosenthal and Jacobson discovered that teachers judged students based on appearance. A neat, attractive look was unconsciously linked to good performance and high motivation. Even when objective academic results were available, teachers assumed that well-groomed children had greater potential.

In 2017, Hernandez-Julian and Peters repeated a similar experiment with college students. Attractive students received higher grades on average. But when instructors couldn’t see their faces (such as in online classes),those same students received lower grades.

Appearance also affects careers. Attractive people tend to earn more. A 2015 study by M. Parrett proved that attractive waiters received more tips — even when service quality was the same. This effect was strongest among female customers, who judged waitresses more on looks than on service.

The halo effect also influences workplace dynamics. Managers often notice and reward the achievements of attractive employees more. When less attractive colleagues improve their performance, their efforts may go unnoticed, leading to demotivation.

The bias strongly affects recruitment. Phil Rosenzweig, in his book The Halo Effect … and the Eight Other Business Delusions, cites statistics showing that HR departments give preference to candidates from prestigious universities. Even when such applicants are less suitable, the reputation of the institution outweighs other factors.

The halo effect doesn’t just apply to people. It also affects how we judge products and companies. Rosenzweig notes that Cisco’s reputation rose and fell with its profits. As long as the company was successful, analysts praised its customer focus. When profits dropped, they criticized the same company for neglecting customers — though its actual behavior likely hadn’t changed much.

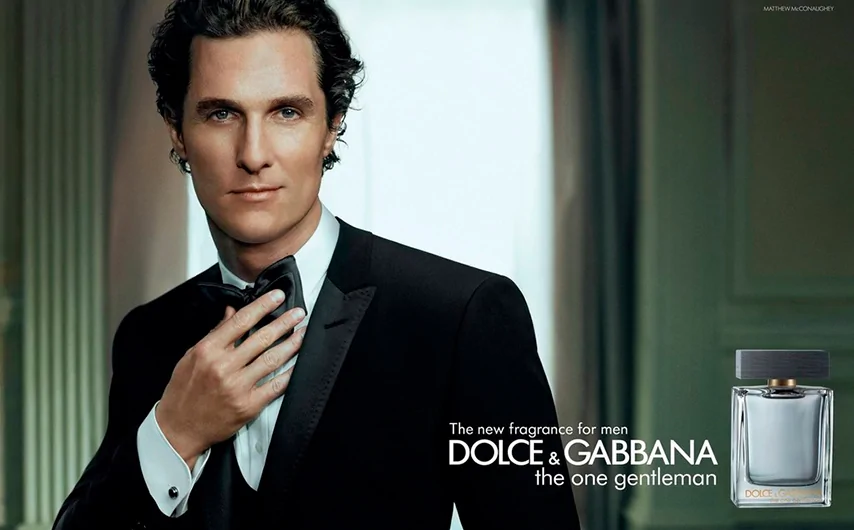

The halo effect can also be harnessed. Companies often collaborate with celebrities to boost their products. The star’s positive image transfers to the brand, increasing sales. A 2014 study showed that many consumers believe a product must be good if a celebrity endorses it. Sales of promoted products can rise several times thanks to such partnerships.

But there are risks. The brand and the celebrity share one reputation. If the celebrity is caught in a scandal, the company suffers too — as happened with Subway and Jared Fogle. Another example: fashion brand St. John ended its contract with Angelina Jolie when her personal fame began to overshadow the company itself.

Even without celebrities, brands use attractive models. Consumers are more likely to trust such advertising, especially in cosmetics. In 2024, a study found that social media filters make both people and the products they promote appear more attractive — influencing purchase decisions.

Other research shows that doctors perceive attractive patients as healthier, sometimes overlooking symptoms. As a result, illnesses are diagnosed later.

Even courts are not immune. In 1974, psychologist Michael Efran showed that juries gave lighter sentences — and sometimes acquittals — to attractive defendants. A year later, other researchers confirmed this effect. The only exception was when the crime itself was linked to appearance (such as fraud),in which case attractive defendants were punished more harshly. Victim appearance also mattered: attractive women received more sympathy from jurors.

In 2009, researchers proved that the halo effect plays a major role in politics. Politicians with more childlike faces are perceived as less competent and struggle more in elections. Those with serious features more easily gain voters’ trust.

The effect even influences what we eat. In 2015, a study showed that people rated identical chocolate higher when it was labeled “organic.” Participants said it tasted better and seemed healthier, even though it was the same product.

The Reverse Halo: The Horn Effect

The opposite of the halo effect also exists — the “horn effect.” A negative first impression is very hard to change. People focus on a person’s flaws and overlook their strengths. A 2014 study confirmed this phenomenon.

The horn effect often makes job hunting harder. Many HR managers admit to rejecting candidates simply because they dislike their appearance. Less competent but more attractive applicants may be chosen instead. Factors like being overweight, tattoos, piercings, hair texture, or unusual hair colors can reduce career opportunities.

How to Resist the Halo Effect

It is possible to resist the halo effect. Psychologists recommend the following strategies:

- Focus on facts. Before making a decision, ask yourself if you have enough objective information about the person, brand, or product.

- Structure your evaluation. Assess each trait separately. Avoid transferring judgments from one characteristic to another.

- Pause before deciding. Give yourself time to think and compare options. This reduces the chance of being influenced by the halo effect.

- Use A/B testing whenever possible, especially in professional settings. This method replaces subjective attractiveness with objective, verifiable data. Marketers rely heavily on it.

Companies also develop defenses against the halo effect. Increasingly, they use unretouched images or models with non-standard appearances in advertising. In recruitment, “blind interviews” are gaining popularity — omitting photos, university names, and other personal details to ensure fairer hiring decisions.

Conclusion

The halo effect is a cognitive bias that affects everyone. We really do “judge by appearance.” It’s one of the quirks of the human brain. Its presence in our lives is inevitable: it influences education, career, health, politics, and even justice. Wherever people are evaluated, the halo effect appears — even when assessing brands or products instead of individuals.

The best way to counteract it is awareness. By recognizing the halo effect, we can make more objective, fact-based decisions instead of relying on first impressions.

At the same time, you can also use it to your advantage. If you’re preparing for an important meeting, interview, or negotiation, pay attention to your appearance. A strong first impression can work in your favor for a long time.