The term “ego” comes up constantly in everyday conversations. Some complain about their partner’s or boss’s inflated ego, while others are advised to tame their own. Yet very few people truly understand what this concept means. In this article, we’ll explore what the ego is from a scientific perspective and how to interact with this part of your personality in a healthy way.

The Definition of Ego in Psychology

The concept of the ego in psychology has existed for more than a century. Our modern understanding of the term differs significantly from the ideas formed in the early 20th century.

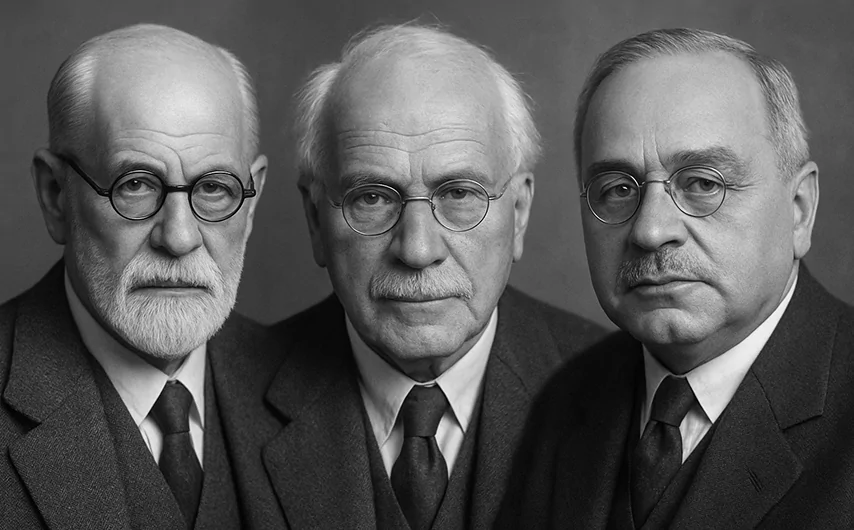

Freud, Jung, and Classical Psychoanalysis

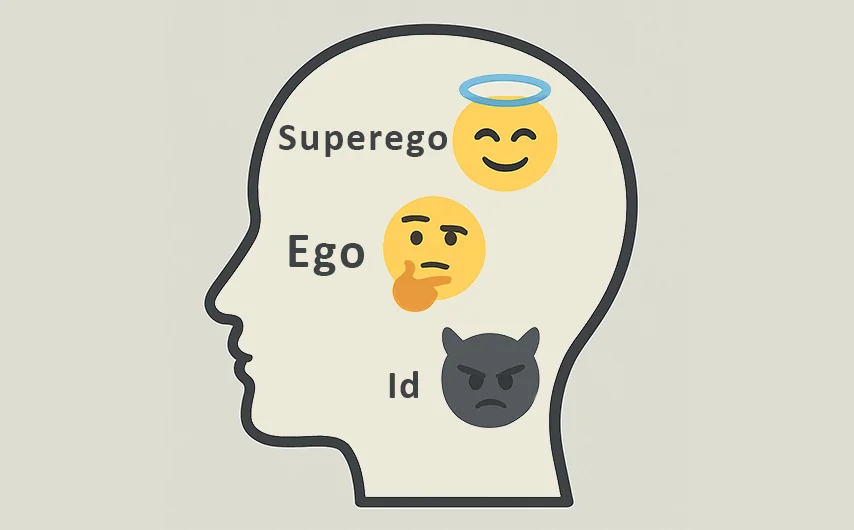

Sigmund Freud created the first systematic theory of the ego as part of his structural model of the psyche. According to this model, the “Ego” is the part of our mind that mediates between the primitive desires of the “Id” and the moral demands of the “Superego.” Freud described the ego through the metaphor of a rider trying to control the unruly horse of unconscious drives.

According to Freud, the ego operates based on the principles of reality and rationality. This means that this mental structure takes external circumstances and social norms into account when satisfying needs. Unlike the Id, which seeks immediate gratification, the ego is capable of delaying satisfaction and finding compromises between desires and possibilities.

Carl Gustav Jung offered a slightly different perspective on the nature of the ego. In his theory, the ego represents the center of consciousness—but not of the entire psyche. Jung emphasized the ego’s limitations compared to the total personality, which includes vast areas of the unconscious. Over-identification with the ego, he believed, cuts a person off from the deeper sources of psychic energy and creativity.

Alfred Adler linked the development of the ego with a person’s social environment. In his view, the ego forms through overcoming feelings of inferiority and striving for significance within society. Adler was the first to highlight the role of social factors in shaping personality, moral principles, and character traits.

Modern Interpretations

Modern psychology views the ego through multiple perspectives. The cognitive approach defines the ego as a system of self-representations — beliefs about one’s own abilities, limitations, values, and place in society.

Humanistic psychology contributed to understanding the positive aspects of the ego. Representatives of this school see a healthy ego as essential for self-actualization. Without a stable sense of self, a person cannot realize their potential or build fulfilling relationships with others.

Some psychologists suggest viewing the ego as a temporary structure of consciousness — one that can expand and transform. This view doesn’t deny the ego’s importance in everyday life but emphasizes the possibility of moving beyond its habitual boundaries.

How the Concept of Ego Became Distorted in Everyday Speech

Everyday use of the word “ego” differs greatly from its scientific meaning. In casual speech, it has become synonymous with arrogance or self-obsession. This interpretation overlooks the ego’s essential functions and its positive influence.

Today, the average person mostly associates the ego with negative personality traits. It’s often spoken of as something bad that must be “tamed,” “suppressed,” or even “destroyed.” This misunderstanding replaces the psychological concept with moral judgments and negative traits such as egocentrism.

In psychology, however, the ego is seen as a vital component of the psyche — without it, normal functioning would be impossible. Problems arise not from the existence of the ego itself, but from disruptions in its development or functioning.

Psychological Mechanisms of the Ego

The functioning of the ego involves numerous interconnected processes that help a person adapt to life events and changes in their environment. Some of these processes operate automatically, beyond conscious control, forming the basis for self-perception and interaction with the world.

Main Functions of the Ego

Self-regulation allows a person to control impulsive urges and act according to long-term goals. This ability develops gradually from childhood and continues throughout life. Research shows a direct link between self-regulation and life success.

A healthy sense of reality enables distinguishing between events and their subjective interpretations, fantasies and facts. This function allows people to perceive reality accurately and make realistic plans. When it malfunctions, various psychological disorders may arise.

Experience integration unites fragmented experiences into a coherent life narrative. The ego creates a continuous personal story, giving meaning to past experiences and forming a basis for future action. Without this function, we couldn’t learn from what we’ve lived through.

Defense Mechanisms

The ego’s defensive function consists of unconscious strategies aimed at reducing anxiety and maintaining internal balance. Classic defense mechanisms include:

- Repression — removing painful memories or unacceptable desires from consciousness;

- Rationalization — creating logical explanations for emotionally driven behavior;

- Projection — attributing one’s own unacceptable traits to others;

- Sublimation — transforming unacceptable impulses into constructive activity;

- Denial — refusing to acknowledge obvious but painful aspects of reality.

Everyone uses these ego defenses to some extent. Problems arise when they become rigid, inflexible, and distort reality. Mature defenses like sublimation and humor promote adaptation, while denial can create serious life difficulties.

Ego and Self-Esteem

The formation of self-esteem is closely linked to how the ego functions. A healthy ego maintains a realistic self-image based on an objective assessment of achievements and failures. Such self-esteem remains relatively stable but flexible enough to adjust with new experiences.

Narcissistic traits often arise as a defense against deep-seated insecurity. Behind the grandiose façade lies a fragile ego that constantly needs external validation. Studies show that people with narcissistic tendencies are highly reactive to threats to their self-esteem.

Dependence on external approval becomes problematic when a person bases their self-worth entirely on others’ opinions. This makes self-esteem unstable and vulnerable: every criticism feels catastrophic, while praise brings only fleeting relief before new doubts appear.

On our website, you can take a free narcissism test.

Cognitive Distortions

The ego plays an active role in processing information—often distorting it to preserve a positive self-image. An interesting meta-analysis of multiple studies found that most people tend to distort reality in their favor, exaggerating their abilities and contributions. We typically do this through mechanisms such as:

- Selective attention — noticing only what confirms our self-image;

- Attribution bias — crediting ourselves for success and blaming circumstances or others for failure;

- Superiority effect — overestimating our abilities compared to others and interpreting ambiguous situations in our favor;

- Retrospective bias — reshaping our memories to maintain self-esteem.

These mechanisms form the subjective reality in which we all live—though to varying degrees. Recognizing these distortions is the first step toward a more objective perception of oneself and the world.

When the Ego Gets Out of Control

Ego problems can take many forms, but they always create difficulties for the individual or those around them. An overly inflated or fragile ego interferes with healthy relationships, goal achievement, and life satisfaction.

Touchiness is often the first sign of ego issues. Such a person perceives neutral remarks as personal attacks, reads hostility where none exists, and constantly feels undervalued. This stems from deep insecurity that the ego tries to compensate for through heightened vigilance to potential threats.

On our website, you can take a free self-esteem test.

Aggressive defensiveness manifests as a need to prove superiority. These individuals turn every discussion into a competition, refuse to admit when they’re wrong, and react painfully to others’ successes. Research shows that such behavior often masks a fear of insignificance.

The need for approval makes a person live as if constantly on stage. Every action is calculated based on the anticipated audience reaction. As a result, personal desires take a back seat, fueling new dissatisfaction and an even stronger need to feed the ego.

The Role of Ego in Interpersonal Conflicts

Most interpersonal conflicts are, at their core, ego clashes. Each side defends its self-image, and this defense often becomes more important than the actual subject of disagreement. Understanding this dynamic can shift one’s perspective on conflict.

On our website, you can take a free conflict behavior test.

Typical ego-driven conflict scenarios include personal attacks, escalation due to wounded pride, vindictiveness, and an inability to admit fault.

In workplaces, ego problems create toxic environments. Employees waste energy on intrigue instead of productivity. Managers suppress initiative out of fear of competition.

On our website, you can take a free team role test.

Family relationships suffer when partners focus more on defending their egos than building trust. Every argument becomes a battle for dominance. Admitting fault is seen as weakness rather than maturity.

Extreme Manifestations

Narcissistic personality disorder represents an extreme form of ego dysfunction. People with this condition live in fantasies of their own uniqueness. They demand special treatment, exploit others, and lack empathy. Behind the confident exterior lies an extremely vulnerable ego that constantly needs reinforcement.

Antisocial personality disorder also involves ego pathology but manifests differently. Here, the ego is so detached from moral norms that the person violates others’ rights without remorse. The absence of guilt or empathy makes such individuals dangerous to society.

On our website, you can take a free sociopathy test.

Borderline personality disorder is likewise characterized by an unstable ego. The person lacks a consistent self-image, and their self-esteem may swing dramatically from idealization to self-loathing.

On our website, you can take a free borderline personality disorder test.

Difficulties with self-regulation in various disorders are often linked to ego deficits. Impulsivity, inability to delay gratification, and poor planning all point to underdeveloped regulatory functions of the ego.

How to Control Your Ego

Working with the ego requires balance. The goal is not to suppress or destroy this part of the psyche but to develop mindful awareness of its manifestations. Modern psychology offers several effective approaches:

Mindfulness and Self-Reflection

Regular mindfulness practice helps cultivate awareness of one’s thoughts and emotions. Keeping a journal allows you to track how your ego reacts to recurring triggers. Over time, you’ll begin to notice what sets off ego defenses—hurt feelings, the desire to impress, fear of criticism, and so on. This awareness creates space for more conscious responses.

On our website, you can take a free mindfulness questionnaire.

The “pause technique” helps create space between stimulus and response. Instead of reacting automatically to provocation, take a breath and ask yourself, “What is my ego trying to protect right now?” This simple question can shift perspective and lead to a more constructive reaction. Studies show that mindfulness training reduces aggression and increases empathy.

Cognitive-Behavioral Techniques

Identifying automatic thoughts is a key step in ego work. Many reactions are triggered by rapid, evaluative thoughts that pass unnoticed. Learning to catch these thoughts allows you to challenge and reframe them.

Reframing means looking at a situation from a different angle. For example, instead of thinking, “They deliberately tried to humiliate me,” you might rephrase it as, “Maybe they just expressed their opinion without realizing it would hurt me.” This shift reduces emotional intensity and opens space for dialogue.

The “evidence for and against” technique encourages objective evaluation. Write down all arguments supporting and contradicting your interpretation of an emotional event. You may discover that your initial judgment was distorted by ego defenses.

Self-Compassion and Self-Worth

Developing self-compassion offers an alternative to constantly defending self-esteem. Instead of proving your worth, you learn to treat yourself with warmth and understanding, especially in moments of failure. Imagine what you would say to a close friend in the same situation—and say it to yourself. This builds inner support that’s often easier to give others than ourselves.

Working with the inner critic involves recognizing that the ego uses self-criticism as a misguided form of protection. The logic goes: if I punish myself first, others can’t hurt me. But this strategy leads to chronic stress and depleted energy. Replacing harsh self-criticism with constructive feedback is far more effective.

The Mirror Effect in Relationships

Close relationships are the best laboratory for ego work. A partner often reflects the aspects of ourselves we refuse to acknowledge. What irritates us most in others frequently points to our own unresolved issues.

Using conflict for self-knowledge transforms painful situations into opportunities for growth. Asking “What does this situation reveal about me?” doesn’t mean taking all the blame but helps recognize one’s contribution to relational dynamics.

Practicing vulnerability breaks through the armor of the ego. Admitting fears, doubts, and mistakes to someone close fosters genuine intimacy.

Should the Ego Be Tamed?

The question of whether it is necessary to work on the ego has no unambiguous answer. Contemporary research shows that both an excessively strong and an overly weak ego create problems for psychological well-being.

This study found a U-shaped relationship between narcissism and life satisfaction. People with moderate scores demonstrated the greatest well-being, while the extremes—both grandiose narcissism and its complete absence—were associated with problems. In other words, for a happy life one needs to be moderately “self-loving,” which is directly related to a normal healthy ego.

With low self-esteem, attempts to “reduce the ego” can lead to a worsening of depressive symptoms. Such people, on the contrary, need to strengthen their sense of self-worth and develop the ability to defend their boundaries. Therapeutic work in this case is aimed at building a more stable and positive self-image.

Cultural context also plays an important role. In the individualistic cultures of modern Western countries, a healthy ego is necessary for successful adaptation. In collectivist societies, for example some Asian countries, an excessive emphasis on individuality can create difficulties in many areas of life. There are no universal recipes — it is important to find a balance appropriate to the specific environment.

Healthy Ego vs Dysfunctional

A healthy ego is characterized by flexibility and adaptability. A person is able to control it, acknowledging their achievements and failures without exaggeration. Self-esteem remains relatively stable but open to adjustment based on new experiences. A person with a healthy ego can rejoice in others’ successes without envy, can admit their mistakes, and accept criticism.

A dysfunctional ego manifests in extremes. A person either tries to prove their superiority or chronically devalues themself. Any threat to self-esteem provokes panic or anger. Relationships are used to feed the ego rather than to create genuine intimacy.

It is important to understand that the ego helps orient in the social world, set goals and achieve them, and protect one’s interests. Problems arise not because the ego exists, but because it is unbalanced. The goal of working with the ego is not destruction but conscious management.

Conclusion

The ego is an inseparable part of every person, not a negative character trait. Modern psychology views the ego as a necessary structure of the psyche that provides adaptation to reality, maintenance of identity, and regulation of behavior. The ego helps us set goals and move toward them despite difficulties.

Problems arise not from the presence of the ego as such, but from disruptions in its functioning. Excessive ego creates conflicts and isolation; too weak an ego makes a person vulnerable and dependent. Each person’s task is to develop a healthy, flexible ego capable of performing its functions. The ultimate goal is not to defeat the ego, but to achieve psychological maturity in which one’s ego becomes a skillful tool and an important ally in building a quality, happy life.